Pandas: Python Data Analysis Library

Introduction

Pandas is a Python library for data analysis.

It provides high-performance,

easy-to-use data structures and data analysis tools.

All of it revolves around the DataFrame object,

which is a tabular data structure with labeled axes (rows and columns).

It is similar to a spreadsheet or a SQL table, or the data.frame in R.

Wikipedia describes it as...

Pandas is a software library written for the Python programming language for data manipulation and analysis. In particular, it offers data structures and operations for manipulating numerical tables and time series.

Series

Introduction

Data series in Pandas are similar to lists in Python. They are one-dimensional arrays of data. They can be created from lists or dictionaries. But in Pandas, you always have to have an index, whether specified or not. Let's examine the below code snippet.

Creating a Series

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

alist = [1,2,3,4]

s1 = pd.Series(alist)

s1When you just create a Series object from a list,

a default index is created for you,

starting from 0 and counting up by 1.

Below is the result of the above code snippet.

0 1

1 2

2 3

3 4

dtype: int64You may want to actually specify the index yourself.

To do this you can either create a dictionary,

where the keys are the index values.

It's also possible to create a Series object from a list or np.array,

where it is the same size as the data Series in the same order.

Modifying the above code snippet with a second list of alphabetical characters,

you get the following result.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

alist = [1,2,3,4]

blist = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

s1 = pd.Series(data=alist, index=blist)

s1a 1

b 2

c 3

d 4

dtype: int64You can also create Series from dictionaries. Simply make the keys the index values, and the values associated with the keys the data in the series.

mydict = {'a': 1, 'b': 2, 'c': 3, 'd': 4}

s3 = pd.Series(mydict)

s3And you get the same result as before with two lists.

Accessing an Element in a Series

To access a specific value in a Series object,

you can use the index value the same way you'd access a value in a dictionary or list.

s1['a']

# Output: 1Accessing a value in a series by its index, like s1 from before, gets you 1.

Slice a Series

Series are sliced a bit differently than lists.

Because they have an index of potentially ordinal values,

you can't assume that the index values are sequential.

So instead of using the : operator,

you have two nested brackets,

with the inner brackets containing the index values you want to slice.

s1[ ['a', 'c']]Results in :

a 1

c 3

dtype: int64Now, is the slice taken a copy or reference? Let's find out by modifying the end of the code from before.

s2 = s1[ ['a', 'c']]

s2['a'] = 10

s1['a']The result is 1.

So clearly slicing in pandas copies the data.

Read & Write Files in Pandas

Pandas I/O API

The pandas I/O API is a set of

top level reader functions accessed like pd.read_csv() that

generally return a pandas object.

It is fairly modular so over time it has accumulated a large number of

specialized readers for various formats.

For example, suppose your manager asks you to analyze some data saved in HTML format. As a data scientist, you would then load the data in your Python program using the appropriate pandas function to read the HTML files and perform the analysis.

Some Common File Formats with API References

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

| read_json() | Read JSON files |

| read_csv() | Read CSV files |

| read_html() | Read HTML files |

| read_excel() | Read Excel files |

| read_sql() | Read SQL files |

| to_json() | Write JSON files |

| to_csv() | Write CSV files |

| to_html() | Write HTML files |

| to_excel() | Write Excel files |

| to_sql() | Write SQL files |

| pandas IO tool | * |

- * Set of functions to read/write custom formats of data to handle data in more bespoke ways

Read & Write JSON Files

Pandas can be used in conjunction with JSON files. JSON is a data format that is commonly used for storage and communication of data between systems, particularly on the internet.

Write Pandas Objects to JSON File

To make it easier to start, let's begin by creating a JSON string.

myseries = pd.Series([1,2,3,4], ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'])

myseries.to_json(orient='index')

# Output: '{"a":1,"b":2,"c":3,"d":4}'Using the to_json() method,

with parameter orient='index',

the index becomes the key in the JSON string and the data becomes the value.

To actually write the JSON string to a file,

you can use the to_json() method again,

but this time with the path_or_buf parameter or

the first positional argument with a file path.

myseries = pd.Series([1,2,3,4], ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'])

myseries.to_json('myseries.json', orient='index')Read JSON File into Pandas Object

Now that there's a file to read,

it's possible to read it into a Series object.

It's mainly done using the pd.read_json() method.

myseries = pd.read_json('myseries.json', orient='index')

myseriesWhich results in this nicely formatted table:

| 0 | |

|---|---|

| a | 1 |

| b | 2 |

| c | 3 |

| d | 4 |

Note that because there isn't an obvious indication of the index,

the orient='index' parameter is used again to indicate that the index is the key.

It's also important to note that because there is no pandas object yet,

the read_json() method is called from the abstract pd module,

not a method of a pandas object like a Series or DataFrame.

Further Reading

DataFrame

Basics

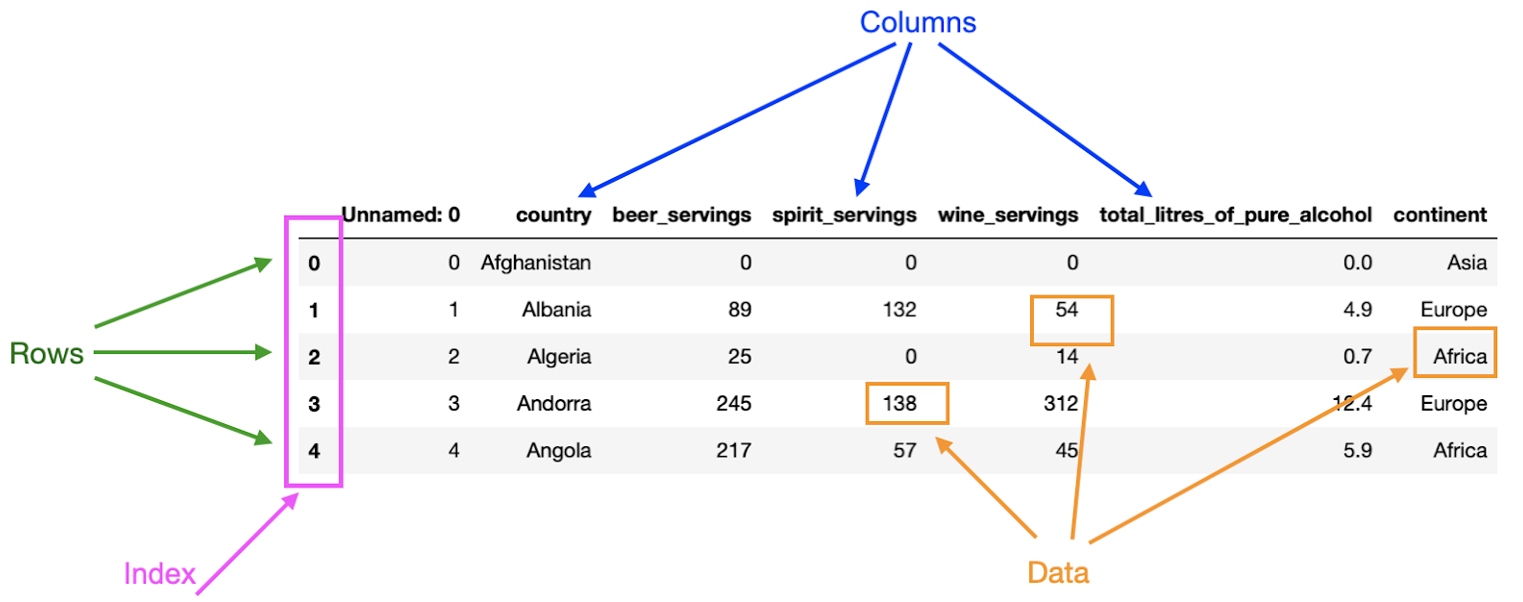

A pandas Dataframe is a 2-dimensional labeled data structure where data is organized in rows & columns. Pandas dataframes have four pricnipal components: rows, columns, index, and data. As shown below in the annotated screenshot.

Given some data, each row represents an observation and each column a variable. In the example above, the first row contains the dirnks consumption for Afghanistan, whereas the second row contains the drinks consumption for Albania.

In a dataframe,

columns can be seen as a label for each measurement taken.

In the image above,

each of the columns describes what data is stored in them;

for example,

the column continent contains the continent of the country.

The index defines the location, address, of each data point in the dataframe. Thus, the index can be used to access data in a dataframe. In the image from before, the first column contains the index of the dataframe. Columns also have an index: the column name. Therefore, the entry "Afghanistan" in the first row has row index 0 and column index "country".

Finally, the data is simply the information stored in the dataframe. One particular thing to consider about dataframes is that they can contain different types of data. However, a column in a dataframe can only have one data type. Observe the dataframe above. You can determine that the data across the dataframe is of different types: integers and floats. However, the data stored in a single column of the dataframe is always going to be of the same type. For example, all the entries in the column "total_litres_of_pure_alcohol" are of type float.

Exploring a DataFrame

Once you have defined or imported your dataframe in your program, it is important that you become familiar with your data. Pandas offer a range of functions to facilitate this.

For example, suppose that you have read and saved the dataframe in

the image below in your code as df.

Often,

one of the first things you would like to do is visualize the first few rows of

your dataframe to see what type of data it contains.

This can be achieved by using the head() function, like this:

df.head()| Unnamed: 0 | country | beer_servings | spirit_servings | wine_servings | * | continent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | Afghanistan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | Asia |

| 1 | 1 | Albania | 89 | 132 | 54 | 4.9 | Europe |

| 2 | 2 | Algeria | 25 | 0 | 14 | 0.7 | Africa |

| 3 | 3 | Andorra | 245 | 138 | 312 | 12.4 | Europe |

| 4 | 4 | Angola | 217 | 57 | 45 | 5.9 | Africa |

* total_litres_of_pure_alcohol

By default,

the head() function returns the first five rows of the dataframe.

This number can be changed by passing an integer to the function.

To know the dimensions of your dataframe,

i.e. the number of rows and columns,

you can use the shape attribute, like this:

df.shapeThe output is a tuple with the number of rows as the first element and the number of columns as the second element. In the example above, the dataframe has 193 rows and 8 columns.

You can see that the command returns a tuple containing the number of rows (193) and columns (7) in the dataframe.

To display the data types in each column of your dataframe,

you can use the .info() function, like this:

df.info()This function returns a list of all the columns in your data set and the type of data that each column contains. Here, you can see the data types int64, float64, and object. Int64 and float64 are used to describe integers and floats, respectively. The object data type is used for columns that pandas doesn’t recognize as any other specific type. It means that all of the values in the column are strings.

Create a DataFrame

Using Lists

Let's jump right into an example.

It's possible to create a DataFrame object from [random data via NumPy][np-zk].

Then to give the columns names,

it's possible to pass a list of column names to the columns parameter.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

cols = ['A', 'B', 'C', 'D']

my_array = np.random.randint(0, 100, size=(5,4))

print(my_array)

# Output:

# [[49 81 18 22]

# [ 0 7 29 70]

# [97 19 49 75]

# [50 58 96 34]

# [18 30 7 2]]

df = pd.DataFrame(my_array, columns=cols)

dfThe resulting data frame is this nice table:

| A | B | C | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 46 | 45 | 46 | 96 |

| 1 | 86 | 40 | 98 | 47 |

| 2 | 79 | 11 | 92 | 77 |

| 3 | 28 | 24 | 49 | 61 |

| 4 | 98 | 78 | 42 | 35 |

The first positional argument is the data,

then any number of optional parameters can be passed,

like the columns parameter.

You can even create date ranges using the pd.date_range function to define columns.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

cols = pd.date_range('2019-01-01', periods=4, freq='D')

my_array = np.random.randint(0, 100, size=(5,4))

print(my_array)

# Output:

# [[49 81 18 22]

# [ 0 7 29 70]

# [97 19 49 75]

# [50 58 96 34]

# [18 30 7 2]]

df = pd.DataFrame(my_array, columns=cols)

dfThe resulting data frame is this nice table:

| 2019-01-01 | 2019-01-02 | 2019-01-03 | 2019-01-04 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 46 | 45 | 46 | 96 |

| 1 | 86 | 40 | 98 | 47 |

| 2 | 79 | 11 | 92 | 77 |

| 3 | 28 | 24 | 49 | 61 |

| 4 | 98 | 78 | 42 | 35 |

Performing Operations on Columns

It's possible to perform operations on columns. For example, let's say you want to add a column that is the sum of two other columns.

df['A + B'] = df['A'] + df['B']

dfThe resulting data frame is this nice table:

| A | B | C | D | A + B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 46 | 45 | 46 | 96 | 91 |

| 1 | 86 | 40 | 98 | 47 | 126 |

| 2 | 79 | 11 | 92 | 77 | 90 |

| 3 | 28 | 24 | 49 | 61 | 52 |

| 4 | 98 | 78 | 42 | 35 | 176 |

Using Dictionaries

There are many situations where defining dataframes using dictionaries is more convenient.

import pandas as pd

contact = {'Name': 'john', 'Email': 'john@mit.edu', 'Course': 1}

contacts = {

'Name': ['john', 'jane', 'joe'],

'Email': ['john@mit.edu', 'jane@mit.edu', 'joe@mit.edu'],

'Course': [1, 2, 3]

}

df = pd.DataFrame(contacts)

dfThe keys become the column names. And the values become the rows. Since there can be multiple values for each key, like if a list is used, the order of the values matches the order in all the other lists.

The resulting dataframe is this nice table:

| Name | Course | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | john | john@mit.edu | 1 |

| 1 | jane | jane@mit.edu | 2 |

| 2 | joe | joe@mit.edu | 3 |

Note: The order of the keys in the dictionary is not guaranteed. So the order of the columns in the resulting dataframe is not guaranteed. It's possible to specify the order of the columns by passing a list of column names to the

columnsparameter.

Cleaning Data

Cleaning up NaNs

When dealing with datasets,

it's common to have missing values.

One way to represent missing values is with NaN (not a number).

This can take different meanings depending on the context,

but is generally different from nullish values like None.

Say we create some random data and insert some NaN values.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

cols = list('ABCD')

np.random.seed(seed=1)

myArray = np.random.ranf(size=(5, 4))

myArray[2, 3] = np.nan

myArray[3, 2] = np.nan

df = pd.DataFrame(myArray, columns=cols)

dfThis results in the following dataframe:

| A | B | C | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.417022 | 0.720324 | 0.000114 | 0.302333 |

| 1 | 0.146756 | 0.092339 | 0.186260 | 0.345561 |

| 2 | 0.396767 | 0.538817 | 0.419195 | NaN |

| 3 | 0.204452 | 0.878117 | NaN | 0.670468 |

| 4 | 0.417305 | 0.558690 | 0.140387 | 0.198101 |

There are several ways of dealing with these missing values, besides just leaving them in and dealing with the missing data later.

Dropping NaNs

First is to simply drop an axis (row or column) that contains a NaN value.

df.dropna(axis=1, inplace=True)This results in this dataframe, but now the two columns with NaN values are gone.

| A | B | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.417022 | 0.720324 |

| 1 | 0.146756 | 0.092339 |

| 2 | 0.396767 | 0.538817 |

| 3 | 0.204452 | 0.878117 |

| 4 | 0.417305 | 0.558690 |

The axis parameter specifies whether to drop rows (0) or columns (1).

The inplace parameter specifies whether to

modify the dataframe in place or return a new dataframe.

Filling in Missing Values

An alternative to dropping the NaN values is to fill them in with some other value.

This can be done with the fillna method.

df.fillna(value=0)The value parameter specifies what value to fill in the NaN values with.

In this case it is 0 which gets cast to a float.

| A | B | C | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.417022 | 0.720324 | 0.000114 | 0.302333 |

| 1 | 0.146756 | 0.092339 | 0.186260 | 0.345561 |

| 2 | 0.396767 | 0.538817 | 0.419195 | 0.000000 |

| 3 | 0.204452 | 0.878117 | 0.000000 | 0.670468 |

| 4 | 0.417305 | 0.558690 | 0.140387 | 0.198101 |

Again, the inplace parameter specifies whether to

modify the dataframe in place or return a new dataframe as a view.

Categorical Data

Another common type of data is categorical data, or ordinal data. This is any type of data that isn't inherently numeric. Think of a label or a category like a kind of fruit, an apple, pear or orange. What is the numeric value of an apple?

Encoding Categorical Data

Although there isn't an inherent numeric value to a category, it is possible to encode the categories as numbers and sometimes those numbers can be meaningful in numerical analysis.

One-hot encoding is a common way to encode categorical data. The phrase "one-hot" comes from the fact that only one of the categories is "hot" or "on" at a time. Conversely, one can one-cool encode the data, where only one of the categories is "cool" or "off" at a time. Typicall one-hot gets used more often than one-cool, because it tends to make more sense in most contexts.

Within pandas there's a get_dummies method that can be used to

one-hot encode categorical data. Let's demonstrate this first by

creating a dataframe about fruit types and their price and stock.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

df_dict = {

'fruit': ['Apple', 'Pear', 'Orange', 'Banana'],

'count': [3, 2, 4, 1],

'price': [0.5, 0.75, 1.2, 0.65]

}

df = pd.DataFrame(df_dict)

dfWhich gets us this dataframe:

| fruit | count | price | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Apple | 3 | 0.5 |

| 1 | Pear | 2 | 0.75 |

| 2 | Orange | 4 | 1.2 |

| 3 | Banana | 1 | 0.65 |

Now if we must perform numerical analysis on the fruit,

they need to be one-hot encoded.

Using the get_dummies method, we can do this.

df = (pd.get_dummies(df, columns=['fruit'])

.rename(columns=lambda x: x.replace('fruit_', '')))

dfWhich gets us this dataframe:

| count | price | Apple | Banana | Orange | Pear | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 2 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 4 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 0.65 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Now the fruit types are encoded as numbers and it should be easier to see how the encoding works. A column is made for each possible value of the category. And only one of the columns is "hot" or "on" at a time.

The rest of the code in the previous snippet,

is just about renaming the columns to make them more readable using rename.

By default pandas get_dummies method will prefix the column names

with the original column name and an underscore.

Time & Date

Time & Dates are a common type of data that is used many contexts within pandas. Their nature means that different handling is required to make them useful.

Epoch Time

The first important concept to know is of the epoch time. The epoch time is the number of seconds since January 1st, 1970. This is the time that is used by computers to keep track of time. When you see a date printed on a computer, it is typically the calculated number of years, months, days, hours, etc since the epoch.

UTC

The epoch time is also known as UTC or Coordinated Universal Time. UTC is the time that is used by the world to keep track of time. It is a single standardised time that is used by all countries, and their different time zones are offset from UTC.

ISO 8601

The standard format for dates and times is ISO 8601. This is a standardised way of representing dates and times. It is a string of numbers and letters that can be parsed by computers.

To put it simply, the format is YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM:SSZ.

Where:

YYYYis the yearMMis the monthDDis the dayHHis the hourMMis the minuteSSis the secondSScan be a decimal number soSS.SSSis also valid

Zis the timezone offsetZis UTC+HH:MMis a positive offset from UTC-HH:MMis a negative offset from UTC- So

+01:00is one hour ahead of UTC, and is also Central European Time (CET)

Date & Time Index

To work with time containing data,

we may need to create a DatetimeIndex object.

This is a special type of index that is used to index data by time.

It is a special type of index because it can be used to index data

by a time range, and not just a single time.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

myArray = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7])

mySeries = pd.Series(myArray)

mySeries.index = pd.date_range(start='1/1/19', periods=7)

mySeries.index.dayofweek

# Output: Int64Index([6, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5], dtype='int64')Note that with dayofweek we can get the day of the week

0 indexed, where 0 is Monday and 6 is Sunday.

PLACEHOLDER FOR ACCESS VIA LOC ILOC AND INDEXING

PLACEHOLDER FOR PIVOTS

Join Dataframes

Why Join Dataframes?

In many real world applications, data is presented to you in separate but related structures. Depending on your needs, pandas provides two ways of combining dataframes: unions & joins.

Union

With the union,

you can append the columns of one dataframe to the other.

The union can be achieved with the concat method.

Suppose you have two dataframes: df1 and df2.

df1 = pd.DataFrame({'student_id': ['S1234', 'S4321'], 'name': ['Daniel', 'John']})

df2 = pd.DataFrame({'student_id': ['S3333', 'S4444'], 'name': ['Mary', 'Jane']})Which produces these two tables:

| student_id | name | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | S1234 | Daniel |

| 1 | S4321 | John |

| student_id | name | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | S3333 | Mary |

| 1 | S4444 | Jane |

Since the columns of the two dataframes are the same,

we can use the concat method to combine, put them into a union.

df = pd.concat([df1, df2]).reset_index(drop=True)Which produces this table:

| student_id | name | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | S1234 | Daniel |

| 1 | S4321 | John |

| 2 | S3333 | Mary |

| 3 | S4444 | Jane |

The reset_index method is used to reset the index of the dataframe.

The index in the resulting dataframe is now a new index with both dataframes,

but with the indexing redone in some order.

Join

Sometimes,

you may want to combine columns in different dataframes that contain common values.

This technique is called joining, and is done with the merge method.

When performing a join, the columns containing the common values are called join keys.

The join concept explored here is similar to how joins are done in SQL.

There are four different types of joins: inner, outer, left, and right. Here they will be explained in detail.

Inner Join

An inner join combines two dataframes by matching the join keys.

Usually, inner joins are the default type of join.

Take for example the previous student dataframes.

If you wanted to combine another dataframe containing last names,

with a join key of student_id,

you would use an inner join.

df3 = pd.DataFrame({'student_id': ['S1234', 'S4321'], 'last_name': ['Smith', 'Doe']})

df = pd.merge(df, df3, on='student_id')which results in this table:

| student_id | name | last_name | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | S1234 | Daniel | Smith |

| 1 | S4321 | John | Doe |

Note: That inner joins are only done on data matching the join keys. So the students 'Mary' & 'Jane' are not included in the resulting dataframe, because they do not have a join key in

df3.

Outer Join

An outer join combines two dataframes by matching the join keys, but it also includes all the data from both dataframes. This means that often the resulting dataframe will have nullish values in the case where there are columns from one dataframe not present in the other.

df4 = pd.merge(df2, df3, how='outer', on='student_id')

# Remember df2 is Mary & Jane, df3 is John & Daniel with a last name column

df4which results in this table:

| student_id | name | last_name | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | S3333 | Mary | NaN |

| 1 | S4444 | Jane | NaN |

| 2 | S1234 | Daniel | Smith |

| 3 | S4321 | John | Doe |

Left Join

A left join combines two dataframes by matching the join keys, but it also includes all the data from the left dataframe. This means that often the resulting dataframe will have nullish values in the case where there are columns from the right dataframe not present in the left.

df5 = pd.merge(df2, df3, how='left', on='student_id')

# Remember df2 is Mary & Jane, df3 is John & Daniel with a last name column

df5which results in this table:

| student_id | name | last_name | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | S3333 | Mary | NaN |

| 1 | S4444 | Jane | NaN |

Right Join

A right join combines two dataframes by matching the join keys, but it also includes all the data from the right dataframe. This means that often the resulting dataframe will have nullish values in the case where there are columns from the left dataframe not present in the right.

df6 = pd.merge(df2, df3, how='right', on='student_id')

# Remember df2 is Mary & Jane, df3 is John & Daniel with a last name column

df6which results in this table:

| student_id | name | last_name | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | S1234 | Daniel | Smith |

| 1 | S4321 | John | Doe |

References

Web Links

- Pandas (Software)(from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia)

- Pandas Series (from W3Schools)

- Pandas Dataframe (from pandas.pydata.org documentation)

- Pandas: How to Read and Write Files (from RealPython by Mirko Stojilkovic)

- read_json (from pandas.pydata.org documentation)

- read_csv (from pandas.pydata.org documentations)

- read_html (from pandas.pydata.org documentation)

- read_excel (from pandas.pydata.org documentation)

- read_sql (from pandas.pydata.org documentation)

- to_json (from pandas.pydata.org documentation)

- to_csv (from pandas.pydata.org documentation)

- to_html (from pandas.pydata.org documentation)

- to_excel (from pandas.pydata.org documentation)

- to_sql (from pandas.pydata.org documentation)

- pandas IO tool (from pandas.pydata.org documentation)

- ISO 8601 (from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia)

- Time & Date in Pandas (from pandas.pydata.org)